Alzheimer's disease is one of the world's biggest health problems. Yet, despite the fact millions of people globally are diagnosed with the disease each year, it remains a challenge to treat. This is largely because the underlying causes are still not fully understood.

However, a new study in mice brings us one step closer to understanding what triggers the disease. The researchers have uncovered a specific enzyme that may be behind one of the key features of Alzheimer's.

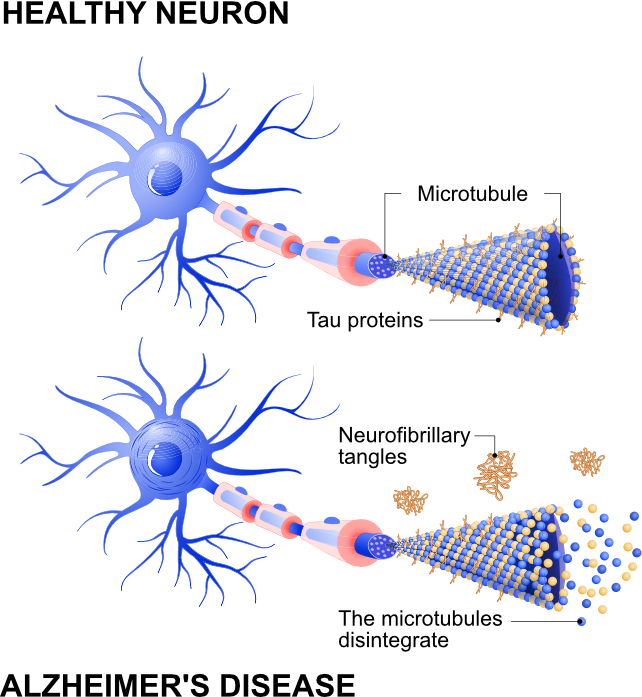

One of the key features of Alzheimer's disease is an accumulation of a harmful protein called tau. In a healthy brain, tau primarily helps to support and stabilise brain cells (neurons). This maintains the structure of these cells, and assists in transporting key substances throughout the neuron so it can function optimally.

But in people with Alzheimer's disease, tau appears to behave abnormally in the brain. Instead of performing its normal function, tau builds up inside neurons and forms twisted clumps, called neurofibrillary tangles.

These tangles can disrupt communication between neurons. Communication between neurons is fundamental for our memory, thinking and behaviour, so any disruption can lead to damage in those areas of the brain.

While scientists have known for decades that tau is involved in the disease, they're still trying to understand exactly why healthy tau misfolds to form these toxic, sticky tangles. This latest study, published in Nature Neuroscience, offers promising new insights into how tau turns toxic in mice.

To mimic Alzheimer's disease, the team of US-based scientists used mice that had been genetically altered to have a build-up of tau in their brains. They found that a specific enzyme may be responsible for turning healthy tau into the toxic tau that accumulates in the brain.

An enzyme is a protein that usually plays a helpful role in the body – making reactions happen faster and more efficiently. But this study found that the enzyme tyrosine kinase 2 (TYK2), which plays a central role in the immune system, adds a special tag to tau.

This tag then appears to make it difficult for the brain to properly clear away unwanted tau. In both mouse models and human cell cultures, the enzyme caused tau to build up and become toxic.

Using genetic tools, the scientists then blocked TYK2 in the mice with Alzheimer's. This resulted in a reduction in the overall amount of tau in the brain – including the amount of harmful, disease-causing tau with the added tag.

The neurons also showed signs of recovery. This suggests that blocking TYK2 could be a way to reduce the toxic tau buildup, and the damage it causes in diseases like Alzheimer's. This could also open new avenues for drug development that could tackle toxic tau in ways that haven't been explored yet.

The finding that lowering or blocking TYK2 could treat Alzheimer's is encouraging, as TYK2 inhibitor drugs have already been tested in humans for a range of different conditions – such as the autoimmune diseases psoriatic arthritis and inflammatory bowel disease.

However, studies are needed to check if TYK2 inhibitors are able to pass the blood-brain barrier. As tau is inside brain cells, it's tough to remove. If these drugs can't reach the brain, they won't be able to lower tau levels in humans and make a difference in Alzheimer's disease.

There's a desperate need for new treatment options for Alzheimer's disease. While two therapies, donanemab and lecanemab, have recently been approved in the UK, they're too expensive for widespread use on the NHS and come with serious side-effects. Many argue that their drawbacks outweigh their benefits.

These treatments focus on removing amyloid plaques, another protein linked to Alzheimer's. But targeting tau, the protein at the heart of this new research, could be a game changer in the search for a more effective treatment.

It should, however, be noted that this research is in its early stages and is still very pre-clinical. Despite mice models being extremely valuable for understanding disease mechanisms, their results don't always translate directly to humans.

More research is needed to see if this technique has the same effect on tau levels in the human brain, whether there are any harmful side-effects – and if blocking TYK2 to clear toxic tau actually improves symptoms of Alzheimer's, such as memory loss.

Targeting TYK2 to reduce toxic tau in the brain shows promise as a potential new approach to treating Alzheimer's. The next steps will be to explore if the same is true in humans.

Rahul Sidhu, PhD Candidate, Neuroscience, University of Sheffield

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.