Bringing bird poop to school is usually frowned upon, but middle schoolers in Chicago are being celebrated as "bonafide biomedical scientists" after one student delivered some special goose droppings to their science club.

With the supervision of researchers from the University of Illinois, this student carefully isolated a bacterium from the goose poop that showed antibiotic activity.

A natural compound produced by this bacterium is wholly new to science, and in the lab, it shows cancer-fighting properties.

Touching bird poop with bare hands is not safe because of all these pathogens, especially during a national outbreak of bird flu, but in this particular case, the student was on a mission for science.

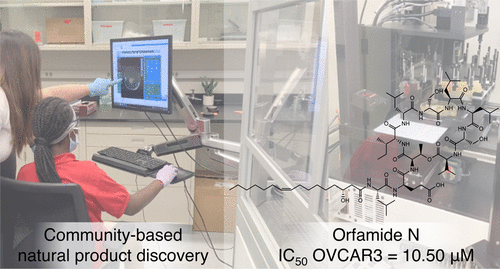

They were part of a 14-week educational outreach program to promote scientific careers with hands-on experience.

The initiative was designed to involve young learners in the search for new antibiotics, and as part of the project, students were asked to explore their neighborhood for new bioactive compounds.

The kids were then taught how to safely grow bacteria and select colonies for further evaluation by university scientists.

The student that brought in the goose feces was able to isolate a species of gram-negative bacteria, Pseudomonas idahonensis. In the lab, researchers found this bacterium could inhibit more than 90 percent of the growth of a gram-positive bacteria species that can cause skin infections.

"Efforts are underway to determine the compound(s) responsible for the original antibiotic activity observed," the team writes in a published and peer-reviewed paper on the discovery.

The middle schooler who found the bird poop is listed as a co-author.

The Pseudomonas bacterium not only showed antibiotic properties, it also produced a novel natural product, called orfamide N, which has not been seen by scientists before. Previously discovered orfamides are known to have useful medical properties, so the team investigated this one further.

In the lab, orfamide N slowed the growth of melanoma and ovarian cancer cells.

As dangerous bacteria around the world grow resistant to today's arsenal of antibiotics, scientists are desperately searching for new medicine, and the natural world is one of the best places to go searching for antibacterial compounds.

The discovery of natural product antibiotics peaked in the mid-1950s, but since then, there has been a dangerous decline in this type of drug development.

Luckily, the natural world is still full of secrets, and some of these unknowns could help us in our battle against major health issues, such as bacterial infections and cancer.

Finding new antibiotics, however, takes years of testing and the failure rate is high. Out of all 14 environmental samples collected in Chicago, just one showed evidence of antibiotic activity, and this may not stand up to future research.

Getting the next generation excited about antibiotic discoveries is a long game, but scientists at the University of Illinois say their recent success story just goes to show that "it is possible to integrate educational outreach programs with high-end natural product discovery."

The study was published in ACS Omega.